Just Say No

Drugs, demons and the limits of "radical pragmatism," being an introduction to the September Material Mysticism

I remember being asked about demons once when I was teaching a Catholic Catechism class at Princeton University as part of a Seminary internship. Back then the mood was more materialist than it is now, and it was a tough case to make. I cited psychologist M. Scott Peck on the subject from his book People of the Lie. He admits that, like most of his colleagues in psychiatry, he didn’t believe in demons earlier in his career because he lacked the experience. Once he gained that experience, however, the demonic could no longer be denied. Peck’s lack of theological training shows in the book (evidenced by his facile critique of Augustine’s privation view of evil), but it remains a profoundly helpful account. “While my experience is insufficient to prove Judeo-Christian myth and doctrine about Satan,” Peck insists, “I have learned nothing that fails to support it….” (203).

That case is not so hard to make anymore. It is encouraging (is that the right word?) to read Robert Falconer’s The Others Within, made well known by this somewhat skeptical and oft-cited review. Falconer’s dramatic healing from a sexually abusive childhood led him to Internal Family Systems psychology, which entails engaging separate parts of the psyche in pursuit of wholeness. Falconer naively assumed all such parts were fragments of benevolent psychic whole, until (like Peck) experience taught him the “no bad parts” ideology was false. “I’m going to crush her like a worm, the same way I’m going to crush you,” says one of these “parts” to him during a session with a female client. This was the “case that changed [his] life.” Falconer came to see that “the trauma model [he was trained by] must be contained in something much, much larger (25). I far prefer Peck’s wisdom in cleaving to a traditional Christian metaphysics when dealing with these entities. Nevertheless, Falconer has the humility to say:

I have no idea about the metaphysical realities behind it, but I think we can say with great certainty that possession and possession-related phenomena are one of the most widely distributed cultural characteristics, found in tribes and cultures all over the planet and as far back in history as we can trace. This phenomenon can destroy people’s lives, and it can also help them changes in wonderful ways [i.e. by moving them from evil toward wholeness]. It is psychologically important — this is absolutely clear. Because of this, I think it is incumbent upon us to take it seriously and study it, not just sneer and walk away (68).

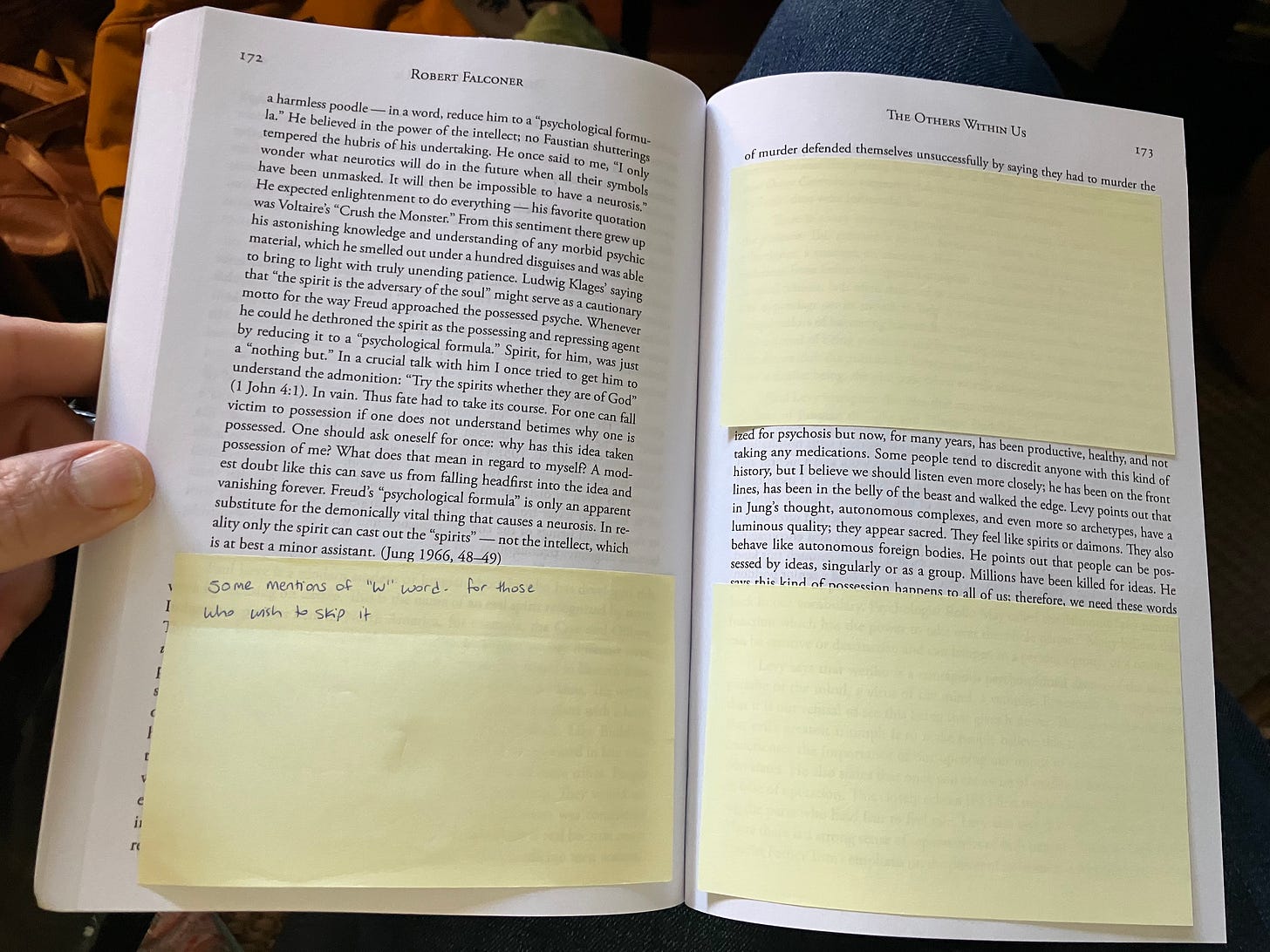

The book is a treasure trove of cultural traditions surrounding possession and interviews that offer strategies for healing, including insights from Christian exorcists (Catholic and Protestant) and the perspectives of Thomas Aquinas, Dionysius the Areopagite, Maggie Ross and William Johnston (some of my favorites). Perhaps the book’s most unintentionally humorous line comes when, commenting on the reality of demonic entities, Falconer concedes, “this does seem to be what the bible says” (235). Still, I found it particularly interesting that the copy I got from the library came with certain sections on Indigenous evil spirits covered up by a previous user. Maybe there is some wisdom to this reticence.

However, I will admit to some confusion that in the face of the reality of evil, Falconer welcomes further exploration, including engaging what are commonly called “machine elves,” namely, the beings encountered by people tripping on DMT. I am as puzzled by accounts of these beings as anyone, and am aware that recorded interactions (and I expect most are not recorded) with such beings are frequently “positive.” Still, wouldn’t Falconer’s “radical pragmatist” approach open to “what works” also be willing to entertain the Catholic exorcist’s advice recorded in the very same book, namely “not to dialogue with them — they are more intelligent than we are and are very tricky” (66)?

Falconer is himself inspired by Peck’s insistence that “explanation is falsity; mystery is truth” in this baffling spiritual arena. Falconer admits, “I want to have that engraved over the door to my house, but still I have this ceaseless urge to explain” (188). But wouldn’t “radical pragmatism” consider there to be serious risk in such an approach? If—as Falconer’s books makes undeniable—evil entities exist, and that they are opposed to goodness, might it not be wise to avoid the drugs that—Falconer’s book also makes undeniable—resolutely expose us to them?

All of this is by way of introducing the September issue of Material Mysticism, an interview with talented writer, Ashley Lande, author of The Things That Would Make Everything Okay Forever: Transcendence, Psychedelics and Jesus Christ. Lande has tripped circles around most presumed experts on psychedelics, and along the way she learned a great deal about evil, and how to be delivered from it. There are aspects of reality, she discovered, to which it is a mercy that we remain closed.

Falconer’s book rightly counsels against fear when confronting the demonic, and on that score, please spare me the claim that Lande’s firm position against psychedelics (which, incidentally, I share) is “fear-based.” On the contrary, Lande’s position, growing from vast experience, has matured into a fearless caution. Lande’s approach to evil reminds me of Teresa of Ávila’s remarks about Satan.

I don’t understand these fears, “The devil! The devil!” when we can say “God! God!” and make the devil tremble….. A fig [a rude gesture in Spanish society at that time] for all the devils, for they shall fear me. (223).

But for both Teresa of Ávila and Ashley Lande, their fearlessness does not come from IFS techniques, “Path” meditation, appeals to the Jungian “Self,” Tibbetan tulpas or ayahuasca retreats (interesting as all that may be), but from the power of the name of Jesus Christ. Psychedelic enthusiasts who mistake Lande’s measured prudence for timidity, and who encourage further exploration into the full pantry of psychedelics, might ask themselves a very pragmatic question: How do you know you’re not like the early M. Scott Peck?

The only reason I can think of for not reading Ashley’s wise commentary on the psychedelic revival in this interview is because you choose to just skip to her remarkable book instead. Better yet, why not do both?

And remember…